(personal underlines)

What has the reparations movement ever done for victims of modern slavery?

Until now it has focused on extracting trillions from European governments in compensation for historic crimes while ignoring horrors still being perpetrated today

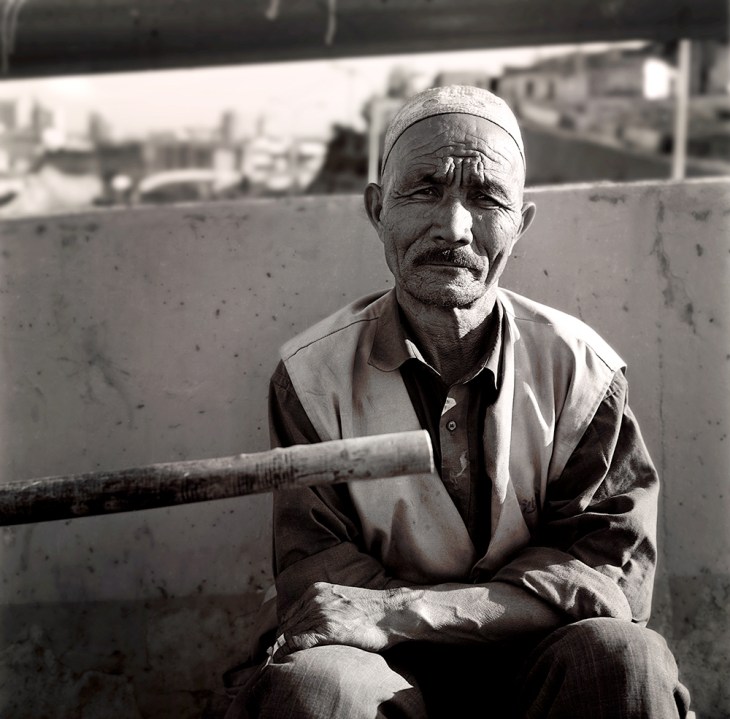

Slavery was – and importantly continues to be – a moral abomination. Its existence in the 21st century is a disgrace. Whole communities such as the Uighurs are subject to forced labour; two years ago it was estimated that 5.8 million people were living in slavery in China. And slavery is a problem much closer to home. Immigrants in the West are also at risk. A student of mine, an Indian national, enquired about the possibility of working at a Brick Lane curry house. He was told that they would ‘employ’ him, but that he would have to surrender his passport and sleep in a locked room on the premises.

There is particular shame about the continuing existence of slavery in London since Britain’s stance against the practice goes back a long way and the determination to eradicate it was exemplary. In 1772, Lord Mansfield ruled that slavery was such an abomination that it would have required positive legislation to permit its existence in Britain. As such legislation had never been passed, it not only became illegal, but, Mansfield ruled, never had been legal in the first place. (Is there an ironic nod in the title of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park, in which the owner of the estate makes his fortune from West Indian slaves?)

In 1807, the Slave Trade Act made it illegal for British ships or subjects to buy or sell enslaved people, and an effective navy squadron was established in West Africa to suppress the trade. By 1845 this was one of the largest fleets in the world. The 1833 Slavery Abolition Act granted emancipation to hundreds of thousands in most British colonies. It took much of the rest of the world rather longer to get around to it. Oman did not abolish slavery until 1970.

It is surprising how often today’s commentators refer to colonialism and slavery as equal evils. That may have been true about Belgian imperialism, but the fact that the British Empire from 1807 devoted a significant part of its energy to suppressing slavery is largely passed over. When, in 2021, the then Prince of Wales remarked at the ceremony marking Barbados becoming a republic that slavery was an ‘appalling atrocity’ that ‘forever stains our history’, the Guardian said that it was ‘a tricky subject for the royal family’ and that it might be the ‘start of grown-up conversation’.

It missed a surely deliberate echo in the King’s words. On 1 June 1840, Prince Albert chose to give his first speech as Prince Consort to the Society for the Abolition of Slavery, and called slavery ‘the desolation of Africa and the blackest stain upon civilised Europe’. The historical opposition of the royal family is of much longer standing, as it happens, than the Guardian, which supported the Confederates in the American civil war and demanded compensation for slave-owners. Those pay-offs were apparently ‘based on the great principles of justice to the planter as well as to the slave. None other could have satisfied the feelings of right-minded people of this country’.

In recent years a movement has sprung up to demand financial reparations for the supposed ongoing effects of slavery on modern-day nations. It does not focus on doing anything for the millions still living in conditions of slavery; nor does it address the responsibility of those countries outside Europe that abolished slavery, often inadequately, within the past 100 years. The main concern is to extract money from European powers. On the surface, this goes against the legal principle of state responsibility that ‘an act does not have a continuing character merely because its effects or consequences continue in time. It must be the wrongful act as such which continues.’

In 2023, a report on reparations for the Brattle Group was published, chaired by the Jamaican UN judge Patrick Robinson, who went on to pass the questionable judgment against Britain’s status in the Chagos Islands. He mentioned this principle of state responsibility but ingeniously dismissed its relevance, since ‘the discriminatory practices that characterised chattelisation continued’. To support this case that all black people suffered and continue to suffer crushing discrimination, he cited the ‘brilliant Caribbean’ Sir Arthur Lewis, who, Robinson noted with justifiable pride, ‘at the young age of 33 became Britain’s first black professor, at the University of Manchester’. That was in 1948, which might have given even Robinson pause for thought about the supposedly all-crushing levels of discrimination in Britain.

Nevertheless, the Brattle group pressed on with its demands for reparations based on discrimination and, rather wonderfully, managed to come up with some specific sums. Britain should pay $24 trillion, of which, by extraordinary coincidence, $9.559 trillion should go to Robinson’s native Jamaica. There are a number of practical objections to this. One is that Jamaica is ranked below Romania and the Ivory Coast on the corruption index, and handing over such a colossal sum might not go to benefit the nation. Second, once Britain had met its obligations by this payment, would Jamaica cease to have any claim on us? It seems extremely unlikely that that would be an end to the matter. Third, there is a lot of historical evidence about the effects of punitive reparations. Did the Brattle report not wonder about how Britons of Caribbean descent would find their lives affected by a popular reaction to the payment?

Finally, there is the indisputable point that the sums are sheer fantasy. Robinson’s report has airily suggested that the payments could be made over ten or 20 years. Even over the longer period, the British government is being asked to double its entire expenditure for two decades. The demands on other countries are still more ludicrous. Portugal is asked to pay $20.582 trillion. Since its government expenditure was only $131.79 billion in 2023, Robinson might have to wait for some time.

Nigel Biggar made a considerable name for himself in 2023 with his exasperated and well-founded Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, a bold attempt to argue the case that imperialism had some benefits. Now he turns his attention to the reparations movement. He specialises in awkward facts, of which there are no shortage in this area. You can raise the temperature in large parts of north London, for instance, by observing that General Dyer, who directed the Amritsar massacre, was actually given Sikh honours after the event. Similarly, when the reparations movement addresses the subject of making payments to Haiti, Biggar is on hand to remind us that Toussaint L’Ouverture, the hero of Haitian liberation, went on owning slaves himself after his own manumission.

Biggar sets out the history of the British anti-slavery campaign, noting a recent and reliable assessment that the effort to suppress the Atlantic slave trade between 1807 and 1867 was probably ‘the most expensive example [of international moral action] recorded in modern history’. He explores, with eye-opening effect, the supposed economic impact of British control over Caribbean territories. A Bengali professor of economic history notes that at the time of independence Jamaica, Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago had incomes per head ‘three to four times that of the long-independent Dominican Republic and Haiti’. Literacy rates in Jamaica were five times that of Haiti. But the subsequent economic histories were very different. Barbados and Jamaica, equally affected by the legacy of slavery, found their paths quite distinct. In 2019, well-governed Barbados achieved a GDP per head more than three times that of Jamaica.

The antics of the reparations industry are amusingly taken apart. The Brattle Report has, it appears, a very flimsy basis for its assertions, including ‘participation in a single telephonic group chat’. The report often misrepresents sources. Robinson says, for instance, that the UK investigation under Dr Tony Sewell into national race and ethnic disparities ‘suggested that black Britons benefited from transatlantic chattel slavery and there should be a focus on the positive aspects of that practice’. Of course the Sewell Report said no such thing.

One of the intellectual powerhouses (relatively speaking) of the reparations movement, Sir Hilary Beckles, has his claims in his book Britain’s Black Debt closely examined, and, strikingly, his extravagant attempts to minimise the atrocities committed by African leaders engaged in the slave trade and present them as early exponents of human rights. ‘The West African custom of burying “servants” alive with their dead master,’ Biggar mildly observes in regard to one of Beckles’s worst claims, ‘does rather imply a view of them as violently disposable property.’

These fantastic caperings are a soft target, and an even softer one is the absurd attempts of the Church of England to pre-empt any claims. Much of Biggar’s book is easy to agree with. A few questions, how-ever, remain. One is whether individual families who benefited from the recompense so strongly recommended by the Guardian might consider that they should return some of it. That seems to me quite different to massive shifts in public expenditure. Another is Biggar’s insistence that historical slavery took different forms, and some slaves’ experiences were much worse than others. That of course is true; but the ownership of another human being was, and still is, a moral abomination, as Mansfield rightly stated in 1772. Nothing at all is to be gained by pretending that for some people slavery was not as bad as all that, and, despite Biggar’s qualifications, even to suggest it makes a generally good case vulnerable to being dismissed as a whole.

Nevertheless, this is an elegantly written and strikingly independent-minded book. I commend Swift Press and its imprint Forum for publishing a work which much of the industry would refuse to touch.