(personal underlines)

The sad demise of the scathing school report

AI versions leave no room for wit or withering put-downs

As the first term of the school year draws to a close, pupils’ reports will soon be landing, encrypted and password-protected, on parents’ smartphones. But once they’ve finally managed to open them to find how little Amelia or Noah has been performing, there will be another code for them to crack: what on earth the teachers are actually trying to say about their child.

These days, reports tend to be written with the help of AI software or templates, which makes it impossible to work out how your child is really doing. In our super-sensitive age, many schools now play it safe by couching all comments as positives, and only using approved adjectives from word banks and drop-down menus. The result is that the real meaning gets obscured by a thick fog of bland generalisations, in case it offends a parent or pupil.

Even that time-honoured put-down, ‘Could do better’, has slipped out of use, replaced by gentle hints that it would help if Felix ‘took a more self-directed approach to learning in order to reach his full potential’.

As a parent of two children, now out the other side of the school system, I have noticed this homogenisation getting worse over the years. I’ve been so frustrated by reports that are nothing more than factual descriptions of what my daughters have covered that term in the curriculum – leaving me none the wiser about how they’ve actually coped with it. It’s made me nostalgic for the days when they still had the scope to be character assassinations.

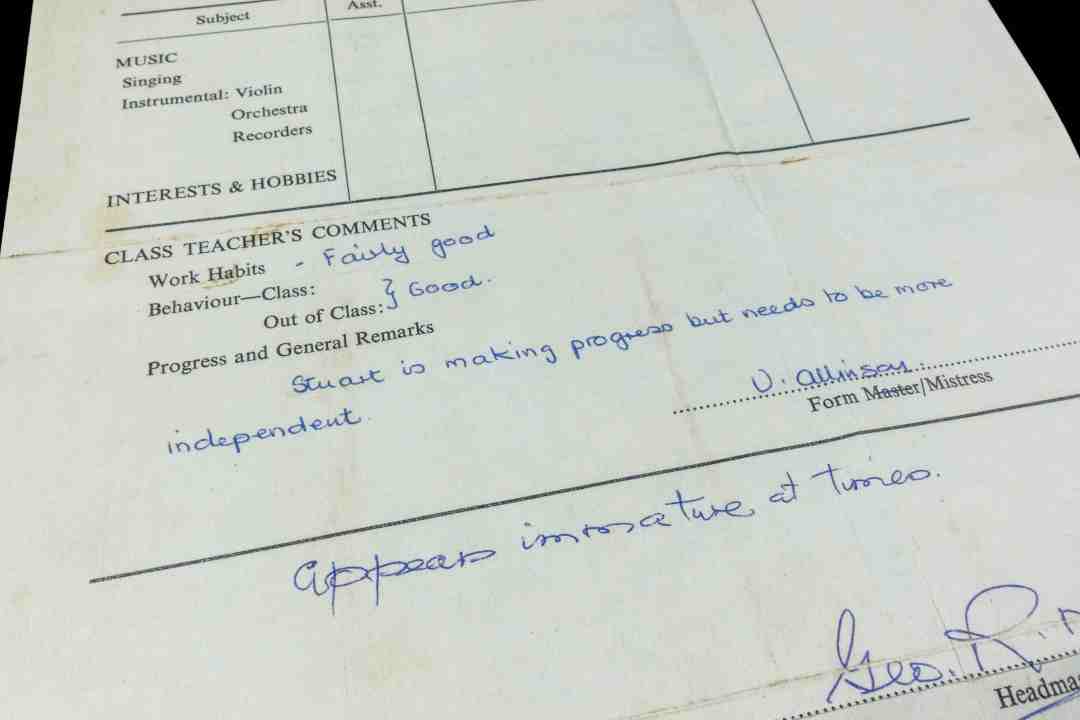

True, the reports of our childhoods could be cruel and despotic, and often said more about the teacher than the pupil. But thanks to the distance of a few decades, I now have a sneaking admiration for the wit that went into some of the withering put-downs, delivered so elegantly in a blue fountain pen.

This nostalgia is also easier because we only hear of the students who either took notice or who were determined to prove these negative judgments wrong and who later became successes – not the pupils whose self-worth never recovered. (I will own up to the fact that 40 years later, I’m still smarting about my house mistress’s description of me as ‘antisocial’ in my first report at Malvern Girls’ College – as if I were busy plotting how to burn the school down from the edge of the hockey pitch.)

But when some of those teachers’ scathing remarks did do the trick of getting pupils to achieve more, it’s hard not to admire their gloriously high-handed prose. Take this pen portrait of the late Shakespearian and Good Life actor Richard Briers. In the 1940s, his headmaster at Rokeby School wrote: ‘It would seem that Briers thinks he is running the school and not me. If this attitude persists, one of us will have to leave.’

Writer and actor Stephen Fry also did very well despite – or perhaps because of – one Uppingham teacher’s judgment that ‘He has glaring faults, and they have certainly glared at us this term. I have nothing more to say’.

My husband Anthony recently found a box of his school reports in the cellar and brought them up for me to read. Still preserved in crisp white envelopes, they covered the time from when he went to prep school, age seven, until he left Ampleforth at 18 – and they were as entertaining as they were eviscerating.

When Anthony was not performing in geography in 1975, for example, his teacher did not spare his parents some home truths, writing that: ‘The genius with which Anthony accredits himself has not been manifest this term, and if he spent more time working and less basking in his imagined success, he might achieve a satisfactory result.’

If his parents were wondering whether their nine-year-old was artistic or not, that idea was brutally kicked into touch by this comment from his art teacher: ‘Anthony rather waits for inspiration to come to him rather than going out to look for it.’

As for his behaviour, that warranted this deft turn of phrase from another master, who wrote: ‘Most staff find in Anthony a deliberate obstinacy not to do as he is told – with a “Je m’en fiche” attitude.’ It’s a phrase I can’t imagine popping up in the school report word banks of 2024.

For Anthony, the good news is that by the time he reached secondary school, these scorchings had the desired effect – mainly because his father summoned him to explain them every time he came home for the holidays.

Extra marks should also go to the masters and mistresses who foresaw the people their pupils would become. In his report home to his father Stanley in 1982, Boris Johnson’s Eton housemaster Martin Hammond already described the qualities which would become familiar to the nation. He wrote of the future PM, then 17: ‘I think he honestly believes that it is churlish of us not to regard him as an exception, one who should be free of the network of obligation which binds everyone else.’

Over at Malvern College, one master who taught Jeremy Paxman in the 1960s also picked up early on the brusque TV presenter’s need to ‘learn tact while not losing his outspokenness’, adding that ‘stubbornness is in his nature’ and ‘could be an asset when directed to sound ends’.

There was also some excellent foresight from Michael Palin’s headmaster at Shrewsbury, who said of the future Python while he was there between 1957 and 1961: ‘He is just a teeny bit pleased with himself. I have noticed a slightly put-on manner of affectation, perhaps a sort of aftermath of his fine performance in the school play. We’re all for a bit of jollity and mild eye-flashing, but he must not try to get away altogether with this slightly facile manner.’

So while you may be bored to tears by your child’s school report when it drops into your inbox this week, there’s one consolation: at least you – or they – are unlikely to be offended. If their teachers really do think they are hopeless cases, never destined to amount to much, you’ll be spared the pain of knowing.

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário