(personal underlines)

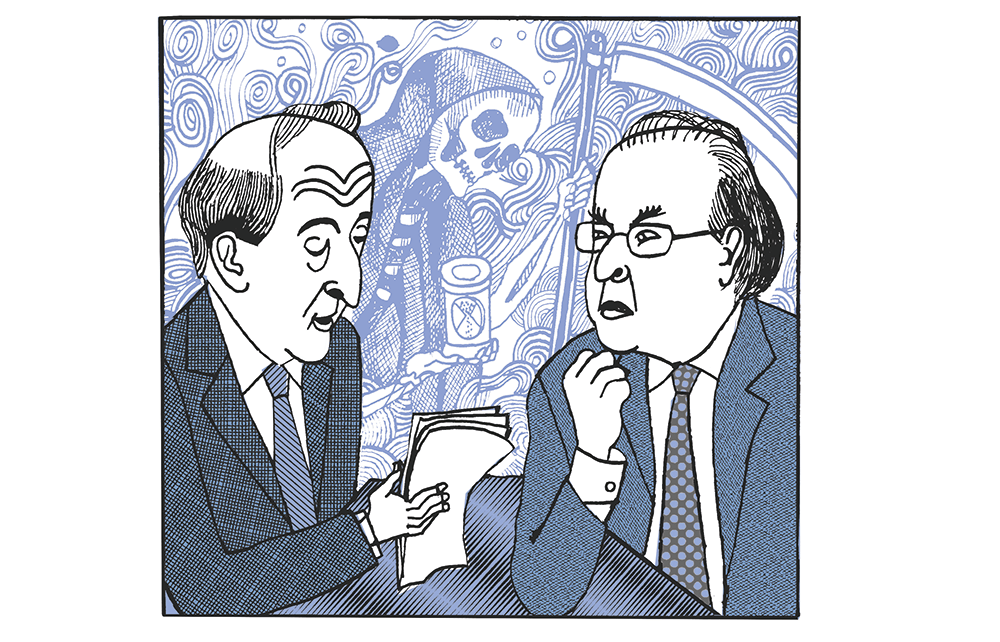

‘Not all suffering can be relieved’: A debate on assisted dying

As Kim Leadbeater’s private member’s bill comes before the Commons, the former justice secretary Lord Falconer (who introduced a similar bill to the Lords) and The Spectator’s chairman Lord Moore debate assisted dying.

CHARLIE FALCONER: The law has effectively broken down. If you assist anybody to take their own life, you’re immediately guilty of an offence, irrespective of motive, and you can be sent to prison for a maximum of 14 years. Even the authorities no longer think that’s enforceable. The Director of Public Prosecutions, the chief prosecutor in the country, has introduced rules that say there are certain circumstances in which he will not prosecute, particularly where somebody assists another to die motivated by compassion and is not a medical professional. That indicates the law is failing and needs to change. When people talk about the moral overreach of the state, they are blind to the fact the state is already there.

CHARLES MOORE: Is that really what this is about though? I don’t believe that what you’re really saying is we just need to clean up a thing in the law. I think you’re saying we need to change a very big thing in society, which is that we now want to help people kill themselves. It is a factual misnomer to call it ‘assisted dying’. This is assisted suicide. And you’re in favour of it.

CF: I’m in favour of somebody taking their own life, which legally is often called suicide, where they are dying already. I am strongly in favour of a situation where, if I have a terminal illness, I am entitled to make my own choice as to the moment of death.

CM: Why are you so nervous of the word suicide?

CF: I used it just then.

CM: You did, but you said, ‘is often called…, etc’. There is a massive moral, not legal, prohibition on suicide because there’s an important thing at stake about human life.

CF: I prefer ‘assisted dying’ because when you talk to people who are in this position, they don’t see it in terms of suicide. They see it in terms of how they will die in the context of terminal illness.

CM: But the problem with ‘assisted dying’ (and it’s an even greater problem with the cant phrase ‘dignity in dying’) is it elides a whole load of other things. There is masses of assisted dying – and so there should be. It’s called palliative care. Opinion polls suggest that a large number are unaware of this distinction. So when you ask ‘Are you in favour of assisted dying?’, if you then explain that that does not include palliative care, the number of people who are in favour of it goes down, which is what you’d expect. There’s wool being pulled over the eyes of the public.

CF I don’t think when people are asked, ‘Are you in favour of a bill that allows people who are terminally ill to be helped to take their own life?’ they think that includes palliative care. But opinion polls shouldn’t determine whether or not parliament passes this. People should look at the details of how the thing works and say whether or not we can improve it. I’m sure we can.

***

CM: Do you not sense the strength of the arguments on the other side?

CF: I sense there are groups who are strongly against it – the Catholic Church, for example. The depth of their feeling is very, very strong, but I do not detect broad support against it. My sense is that most people who come to it without a spiritual or moral view will say: ‘I think it’s probably quite sensible.’

CM: It’s right that there are a lot of religious reasons why people object, but I don’t think that’s why people in general see problems. The arguments of those who have seen the suffering of people and therefore want assisted suicide are important to hear, but there are a lot of people on the other side who also have direct experience of this. There are people in palliative care, for example. There are families with disabilities. I know one wants to avoid the cliché of the slippery slope, but if you trace what’s happened in Oregon, Canada, the Netherlands and so on, you notice that the criteria move. There are extreme cases, which admittedly are untypical, but they do arise. You get conditions of mental illness in which young people are persuaded to end their own lives. There are cases of autism. I’ve read a case of tinnitus. One of the things that’s difficult about this is that most of us, luckily, don’t deal with people who have severe illnesses all the time, so we don’t know what happens in palliative care. I worry people think there is only one kind way out. It isn’t as simple as that.

CF: First, your point that some people in palliative care are against it is right. But equally, some people engaged in palliative care are very strongly in favour of it. Secondly, you imply that a terminally ill bill could lead to people with tinnitus being given an assisted death. That is wrong. You then clump together Oregon, the Netherlands and a variety of other countries. The select committee on health did a report last year in which they confirmed that where a nation or a jurisdiction decides it wants some sort of assisted dying bill, if it starts with a terminal illness bill, as opposed to an unbearable suffering bill, that is where it sticks.

CM: So you would be against an extension beyond terminal illness?

CF: I would. I am against, as a matter of policy, the state assisting people to take their own lives save in the context of terminal illness.

The other point you made was that the proponents of this bill are saying this is the kind way out. Most people won’t want an assisted death. They will want to go on with a maximum palliative care that can be obtained. But everybody you talk to indicates that there are some people, no matter how good the palliative care is, who cannot bear to go on. Sometimes it’s the pain which cannot be dealt with, but sometimes it’s the indignity. Earlier you slightly sneeringly referred to dignity…

CM: I don’t refer sneeringly to dignity. I am critical of the appropriation of the word to your side of the argument.

CF: For some people the idea, for example, of being dependent upon one’s adult children can be something they just cannot bear. They do not want to be a burden.

CM: These wishes at these times are understandable. But I worry about it as a basis of law. It raises something which is not quite understood about suicide, which is the effect it has on other people. I’ve seen this very much with people who’ve committed suicide – nothing to do with assisted suicide, just suicide. One of the sad things that happens when you’re in a mood to commit suicide is that you become, through no fault of your own, solipsistic. Everything’s closing in on you. You think about yourself and you think very badly of yourself. Therefore, it’s hard for them to understand that by killing themselves they cause great pain to others. They often think they’re doing a kindness to others. I’m worried about the balance of the whole of society about persuasion in these matters and where it might lead.

Near us in Sussex is this wonderful thing, the Beachy Head Chaplaincy. Because of the wretched effect of the internet, Beachy Head is now a global suicide destination. People come in huge numbers to kill themselves there. All these chaplains do is walk along up to where people jump and they try to dissuade them. Last year, they dissuaded something like 500 people from jumping. That seems to be a very interesting example of the power of persuasion for good. Almost nobody would say: ‘How dare they try to persuade them not to jump? They have their own right to jump!’ But it’s jolly difficult to kill yourself if people are engaging you in polite conversation. By the same token the other way round, if we create a society in which you are in some circumstances encouraged to kill yourself, we change the moral basis of society. Vulnerable people will be more vulnerable.

CF: You rightly contextualised your remarks on the basis that you are not talking about terminal illness. You’re talking about suicide in a different sort of context. That’s why, as far as I’m concerned, there’s a rock-solid line that the right to be assisted only goes to people who are terminally ill.

***

CM: What’s being proposed is unfair on doctors, because the new law is not asking them to make a medical judgment about the best interests of the patient. It’s asking them to sit in judgment on the patient’s choice.

Lying behind your argument is the idea that choice is the supreme virtue here. One reason people are so upset about death is that they’re used to exercising control, and they find it very hard to be in a situation where they don’t have it. Fundamentally you cannot control the fact that you will die and I worry about the pressures on society if there appears to be a choice on this matter. Our law, our social relations, and our overall moral judgments depend on the idea that we should not intentionally kill one another or help kill one another. If this [the Assisted Dying Bill] comes forward, we are setting up a choice, presented to everybody who faces a terminal illness. This is an unpleasant choice to be confronted with for professionals, for judges, for the families and people involved.

It will also result in exploitation. The sad fact is some people very much want people they know well to die. Another fact is most of the people who are in this situation may not be in a good position to exercise a choice because they are suffering from the drugs they’ve taken, mental distress, tiredness.

CF: You appear to be saying that people should not have a choice when they are terminally ill as to how and when they die. I recognise the need for safeguards in relation to that, but I do not think that is an inherently bad thing. Indeed, the underlying principle of the terminal illness bill that I have introduced is that it is inherently a good thing that you should have a degree of autonomy about how you die.

The second point you made was that if people are given a choice, that choice is subject to exploitation and abuse by others. Completely separately from my bill, when one is ill there are a lot of choices that have to be made, and many of those choices are not the choices of the patient at all. They are made by their doctors, hopefully with consultation, but sometimes not. Those choices are presumably equally exploitable in your book, but have no safeguards whatsoever. It seems to me that if there has to be your treating doctor, an independent doctor and a judge to check that you are not being exploited, that’s a pretty strong safeguard.

And your third point, that people reach what might not be their real view because they’re tired, they’re ill, they’re depressed… People who have had experience of dealing with those who are terminally ill will tell you it’s often very clear what people want. I’m interested in your austere view that people should not have choice in this matter.

CM: It’s not austere. It’s trying to remember that we live in a culture and we live in a society. What’s at stake here is how the whole of society is constructed in the most humane way possible. This is a practical policy thing as well as a moral thing, because it’s a question of what happens next. So, for example, in a National Health Service which is notoriously desperate for money, despite getting more and more all the time, it will be cheaper and in some sense easier for there to be more assisted suicide. In some societies people will say this sort of thing quite openly. In more unpleasant societies they will extend that to the handicapped and so on, because people have a totalitarian idea of ‘What’s the point of somebody who’s not productive?’ You do not want to open the door to that way of looking at things. But you don’t have to open that door. I was distressed by Kim Leadbeater saying that if we don’t get her bill, the choice will be ‘suffering, suicide or Switzerland’. No. It’s insulting to the hospice movement and palliative care to say that and it’s insulting to a lot of non-professionals who look after those they love. Not all pain can be relieved, not all suffering can be relieved.

But nevertheless, there’s a more optimistic way to look at our society. When you and I were young there was much more of an assumption, for example, that nothing much could be done about disability. It was thought that children with Down’s syndrome had to be more or less locked away and couldn’t be integrated into society. Similarly, we have the collective capacity to assist dying, in a real sense. There’s an inner pessimism in your side of the argument, which I’m resisting.

CF: I reject the suggestion that if you introduce a heavily safeguarded assisted dying provision, that is going to lead to people saying: ‘Oh, people who are disabled should just be not treated.’ I repudiate that opening the door in this way will lead to this horrible dystopian picture you create.

***

CM: There are serious questions about the [prognosis of] six months [in order to qualify as ‘terminally ill’]. It’s not often tremendously easy to diagnose terminal illness, particularly within a time frame of six months. Because of the great improvement of drugs, it makes it hard to judge whether ‘six months’ will mean anything. You will have an odd situation if your bill is passed (or Leadbeater’s) in which people actually want a terminal diagnosis because they’ve decided this would then allow them to have assisted suicide.

CF: It requires a judgment, but a lot of medical care requires a judgment. In the majority of cases it will be plain that the person’s death is coming in the next few days or weeks. This is not really a problem. You identify a group of people who have a chronic condition that is not immediately going to kill them, but they want a diagnosis of six months or less so they can avail themselves of assisted suicide. You’ve created this scenario. Do you have evidence that that’s what’s happening?

CM: I’m sorry to go back to the phrase, but there is a slippery slope in these things because there are a lot of people who want [assisted dying] who have a fundamentally different approach to human life to what I do and perhaps even what you do. They actually want there to be more euthanasia. It’s not just that they’re trying to remedy a desperate situation. They think there’s something wrong about people existing in conditions that are suboptimal and they would like the world to be rid of people like that. The Voluntary Euthanasia Society, which Dignity in Dying emerged from, has a background in the history of eugenics.

CF: The idea that a bill where two doctors and a High Court judge have to approve it is, in fact, the thin end of a eugenic wedge is absolute nonsense. It is such an inflammatory and unfair way to oppose the bill.

CM: No, it’s not inflammatory. Although I don’t perhaps have quite your reverence for the judiciary. We are giving the power of life and death to judges. I’m sure they’ll act conscientiously, but it worries me. You’ve tried to separate the arguments for your bill from wider arguments, but am I not on to something about the cultural effect of helping people kill themselves? We often love criticising taboos, but they are very important things. They restrain us from doing the things we tend to want to do.

CF: The way you’re framing your opposition is so overdone. You are sensible and compassionate, and your responses are probably the responses of most people in this country. Yet at the same time you wrap up your opposition to the bill in risks that don’t really exist. Why do you think the law cannot reflect a sensible practice of distinguishing between the compassionate and a much more pernicious sort of behaviour? Is the difference between us my faith that the law can manage it?

CM: The scales will be pushed the wrong way. It will encourage some bad actors to act worse, and it will put more pressure on the weak and ill to feel that it would be a kinder thing for them to go. It has wider consequences. One has to see it as a whole and as a whole it’s a move in the wrong direction.

CF: Yes, you do have to see it as a whole. The consequence will be that you will reduce quite considerably the suffering of a significant number of people. You will not remotely encourage bad actors, nor will you put pressure on the vulnerable, because of the level of safeguarding. It will bring compassion where at the moment there is only confusion and terrible compulsion.

CM: There isn’t only confusion and terrible compulsion. There’s a great deal of good done. That’s what we need to bolster.

CF: You set the kindness and compassion in the palliative care movement against those who want an earlier moment of death when they are terminally ill. There is no conflict between the two. Both can coexist.

This is an edited transcript of the conversation. Watch the full debate on SpectatorTV at spectator.co.uk/tv.

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário