Get Ready for the Great Urban Comeback

Visionary responses to catastrophes have changed city life for the better.

On December 16, 1835, New York’s rivers turned to ice, and Lower Manhattan went up in flames. Smoke had first appeared curling through the windows of a five-story warehouse near the southern tip of Manhattan. Icy gales blew embers into nearby buildings, and within hours the central commercial district had become an urban bonfire visible more than 100 miles away.

To hear more feature stories, get the Audm iPhone app.

Firefighters were helpless. Wells and cisterns held little free-flowing water, and the rivers were frozen solid on a night when temperatures plunged, by one account, to 17 degrees below zero. The fire was contained only after Mayor Cornelius Lawrence ordered city officials to blow up structures surrounding it, starving the flames of fuel.

A new Manhattan would grow from the rubble—made of stone rather than wood, with wider streets and taller buildings. But the most important innovation lay outside the city. Forty-one miles to the north, New York officials acquired a large tract of land on both sides of the Croton River, in Westchester County. They built a dam on the river to create a 400-acre lake, and a system of underground tunnels to carry fresh water to every corner of New York City.

The engineering triumph known as the Croton Aqueduct opened in 1842. It gave firefighters an ample supply of free-flowing water, even in winter. More important, it brought clean drinking water to residents, who had suffered from one waterborne epidemic after another in previous years, and kick-started a revolution in hygiene. Over the next four decades, New York’s population quadrupled, to 1.2 million—the city was on its way to becoming a fully modern metropolis.

The 21st-century city is the child of catastrophe. The comforts and infrastructure we take for granted were born of age-old afflictions: fire, flood, pestilence. Our tall buildings, our subways, our subterranean conduits, our systems for bringing water in and taking it away, our building codes and public-health regulations—all were forged in the aftermath of urban disasters by civic leaders and citizen visionaries.

Natural and man-made disasters have shaped our greatest cities, and our ideas about human progress, for millennia. Once Rome’s ancient aqueducts were no longer functional—damaged first by invaders and then ravaged by time—the city’s population dwindled to a few tens of thousands, reviving only during the Renaissance, when engineers restored the flow of water. The Lisbon earthquake of 1755 proved so devastating that it caused Enlightenment philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau to question the very merits of urban civilization and call for a return to the natural world. But it also led to the birth of earthquake engineering, which has evolved to make San Francisco, Tokyo, and countless other cities more resilient.

Derek Thompson: Hygiene theater is a huge waste of time

America’s fractious and tragic response to the COVID-19 pandemic has made the nation look more like a failed state than like the richest country in world history. Doom-scrolling through morbid headlines in 2020, one could easily believe that we have lost our capacity for effective crisis response. And maybe we have. But a major crisis has a way of exposing what is broken and giving a new generation of leaders a chance to build something better. Sometimes the ramifications of their choices are wider than one might think.

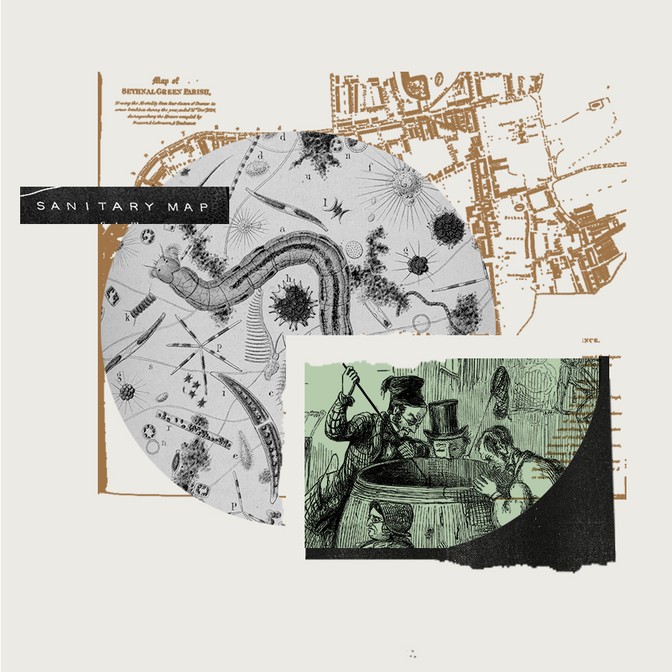

The Invention of Public Health

As Charles Dickens famously described, British cities in the early years of the Industrial Revolution were grim and pestilential. London, Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds—they didn’t suffer from individual epidemics so much as from overlapping, never-ending waves of disease: influenza, typhoid, typhus, tuberculosis. They were also filled with human waste. It piled up in basements, spilled from gutters, rotted in the streets, and fouled rivers and canals. In Nottingham—the birthplace of the Luddite movement, which arose to protest textile automation—a typical gallon of river water contained 45 grams of solid effluent. Imagine a third of a cup of raw sewage in a gallon jug.

Read: Is ‘progress’ good for humanity?

No outbreak during the industrial age shocked British society as much as the cholera epidemic in 1832. In communities of 100,000 people or more, average life expectancy at birth fell to as low as 26 years. In response, a young government official named Edwin Chadwick, a member of the new Poor Law Commission, conducted an inquiry into urban sanitation. A homely, dyspeptic, and brilliant protégé of the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham, Chadwick had farsighted ideas for government. They included shortening the workday, shifting spending from prisons to “preventive policing,” and establishing government pensions. With a team of researchers, Chadwick undertook one of the earliest public-health investigations in history—a hodgepodge of mapmaking, census-taking, and dumpster diving. They looked at sewers, dumps, and waterways. They interviewed police officers, factory inspectors, and others as they explored the relationship between city design and disease proliferation.

The final report, titled “The Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain,” published in 1842, caused a revolution. Conventional wisdom at the time held that disease was largely the result of individual moral shortcomings. Chadwick showed that disease arose from failures of the urban environment. Urban disease, he calculated, was creating more than 1 million new orphans in Britain each decade. The number of people who had died of poverty and disease in British cities in any given year in the 1830s, he found, was greater than the annual death toll of any military conflict in the empire’s history. The cholera outbreak was a major event that forced the British government to reckon with the costs of industrial capitalism. That reckoning would also change the way Western cities thought about the role of the state in ensuring public health.

The source of the cholera problem? All that filthy water. Chadwick recommended that the government improve drainage systems and create local councils to clear away refuse and “nuisance”—human and animal waste—from homes and streets. His investigation inspired two key pieces of national legislation, both passed in 1848: the Public Health Act and the Nuisances Removal and Diseases Prevention Act. A new national Board of Health kept the pressure on public authorities. The fruits of engineering (paved streets, clean water, sewage disposal) and of science (a better understanding of disease) led to healthier lives, and longer ones. Life expectancy reached 40 in England and Wales in 1880, and exceeded 60 in 1940.

Chadwick’s legacy went beyond longevity statistics. Although he is not often mentioned in the same breath as Karl Marx or Friedrich Engels, his work was instrumental in pushing forward the progressive revolution in Western government. Health care and income support, which account for the majority of spending by almost every developed economy in the 21st century, are descendants of Chadwick’s report. David Rosner, a history and public-health professor at Columbia University, puts it simply: “If I had to think of one person who truly changed the world in response to an urban crisis, I would name Edwin Chadwick. His population-based approach to the epidemics of the 1830s developed a whole new way of thinking about disease in the next half century. He invented an entire ethos of public health in the West.”

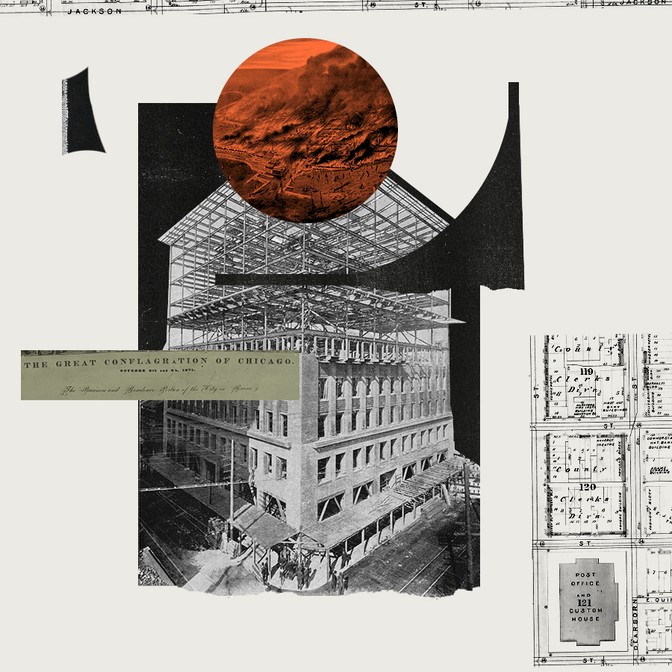

Why We Have Skyscrapers

Everyone knows the story: On the night of October 8, 1871, a fire broke out in a barn owned by Patrick and Catherine O’Leary in southwest Chicago. Legend blames a cow tipping over a lantern. Whatever the cause, gusty winds drove the fire northeast, toward Lake Michigan. In the go-go, ramshackle era of 19th-century expansion, two-thirds of Chicago’s structures were built of timber, making the city perfect kindling. In the course of three days, the fire devoured 20,000 buildings. Three hundred people died. A third of the city was left without shelter. The entire business district—three square miles—was a wasteland.

On October 11, as the city smoldered, the Chicago Tribune published an editorialwith an all-caps headline: cheer up. The newspaper went on: “In the midst of a calamity without parallel in the world’s history, looking upon the ashes of thirty years’ accumulations, the people of this once beautiful city have resolved that chicago shall rise again.” And, with astonishing speed, it did. By 1875, tourists arriving in Chicago looking for evidence of the fire complained that there was little to see. Within 20 years, Chicago’s population tripled, to 1 million. And by the end of the century, the fire-flattened business district sprouted scores of buildings taller than you could find anywhere else in the world. Their unprecedented height earned these structures a new name: skyscraper.

The Chicago fire enabled the rise of skyscrapers in three major ways. First, it made land available for new buildings. The fire may have destroyed the business district, but the railway system remained intact, creating ideal conditions for new construction. So much capital flowed into Chicago that downtown real-estate prices actually rose in the first 12 months after the fire. “The 1871 fire wiped out the rich business heart of the city, and so there was lots of money and motivation to rebuild immediately,” Julius L. Jones, an assistant curator at the Chicago History Museum, told me. “It might have been different if the fire had just wiped out poor areas and left the banks and business offices alone.” What’s more, he said, the city used the debris from the fire to extend the shoreline into Lake Michigan and create more land.

Derek Thompson: The workforce is about to change dramatically

Second, a combination of regulatory and technological developments changed what Chicago was made of. Insurance companies and city governments mandated fire-resistant construction. At first, Chicago rebuilt with brick, stone, iron. But over time, the urge to create a fireproof city in an environment of escalating real-estate prices pushed architects and builders to experiment with steel, a material made newly affordable by recent innovations. Steel-skeleton frames not only offered more protection from fire; they also supported more weight, allowing buildings to grow taller.

Third, and most important, post-fire reconstruction brought together a cluster of young architects who ultimately competed with one another to build higher and higher. In the simplest rendition of this story, the visionary architect William Le Baron Jenney masterminded the construction of what is considered history’s first skyscraper, the 138-foot-tall Home Insurance Building, which opened in 1885. But the skyscraper’s invention was a team effort, with Jenney serving as a kind of player-coach. In 1882, Jenney’s apprentice, Daniel Burnham, had collaborated with another architect, John Root, to design the 130-foot-tall Montauk Building, which was the first high steel building to open in Chicago. Another Jenney protégé, Louis Sullivan, along with Dankmar Adler, designed the 135-foot-tall Wainwright Building, the first skyscraper in St. Louis. Years later, Ayn Rand would base The Fountainhead on a fictionalized version of Sullivan and his protégé, Frank Lloyd Wright. It is a false narrative: “Sullivan and Wright are depicted as lone eagles, paragons of rugged individualism,” Edward Glaeser wrote in Triumph of the City. “They weren’t. They were great architects deeply enmeshed in an urban chain of innovation.”

It is impossible to know just how much cities everywhere have benefited from Chicago’s successful experiments in steel-skeleton construction. By enabling developers to add great amounts of floor space without needing additional ground area, the skyscraper has encouraged density. Finding ways to safely fit more people into cities has led to a faster pace of innovation, greater retail experimentation, and more opportunities for middle- and low-income families to live near business hubs. People in dense areas also own fewer cars and burn hundreds of gallons less gasoline each year than people in nonurban areas. Ecologically and economically, and in terms of equity and opportunity, the skyscraper, forged in the architectural milieu of post-fire Chicago, is one of the most triumphant inventions in urban history.

Taming the Steampunk Jungle

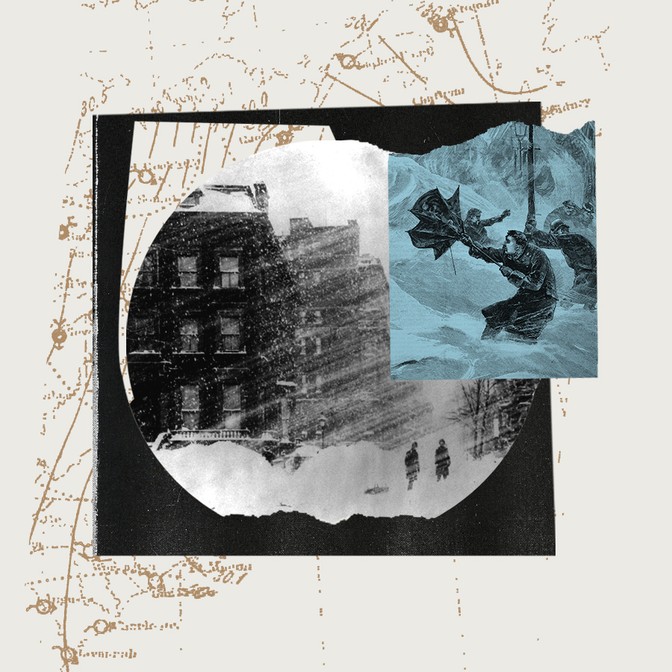

March 10, 1888, was a gorgeous Saturday in New York City. Walt Whitman, the staff poet at The New York Herald, used the weekend to mark the end of winter: “Forth from its sunny nook of shelter’d grass—innocent, golden, calm as the dawn / The spring’s first dandelion shows its trustful face.” On Saturday evening, the city’s meteorologist, known lovingly as the “weather prophet” to local newspapers, predicted more fair weather followed by a spot of rain. Then the weather prophet went home and took Sunday off.

Meanwhile, two storms converged. From the Gulf of Mexico, a shelf of dark clouds soaked with moisture crept north. And from the Great Lakes, a cold front that had already smothered Minnesota with snow rolled east. The fronts collided over New York City.

Residents awoke on Monday, the day Whitman’s poem was published, to the worst blizzard in U.S. history. By Thursday morning, the storm had dumped more than 50 inches of snow in parts of the Northeast. Snowdrifts were blown into formations 50 feet high. Food deliveries were suspended, and mothers ran short on milk. Hundreds died of exposure and starvation. Like the Lisbon earthquake more than a century before, the blizzard of 1888 was not just a natural disaster; it was also a psychological blow. The great machine of New York seized up and went silent. Its nascent electrical system failed. Industries stopped operating. “The elevated railways service broke down completely,” the New York Weekly Tribune reported on March 14:

The street cars were valueless; the suburban railways were blocked; telegraph communications were cut; the Exchanges did nothing; the Mayor didn’t visit his office; the city was left to run itself; chaos reigned.

The New York now buried under snow had been a steampunk jungle. Elevated trains clang-clanged through neighborhoods; along the streets, electrical wires looped and drooped from thousands of poles. Yet 20 years after the storm, the trains and wires had mostly vanished—at least so far as anyone aboveground could see. To protect its most important elements of infrastructure from the weather, New York realized, it had to put them underground.

First, New York buried the wires. In early 1889, telegraph, telephone, and utility companies were given 90 days to get rid of all their visible infrastructure. New York’s industrial forest of utility poles was cleared, allowing some residents to see the street outside their windows for the first time. Underground conduits proved cheaper to maintain, and they could fit more bandwidth, which ultimately meant more telephones and more electricity.

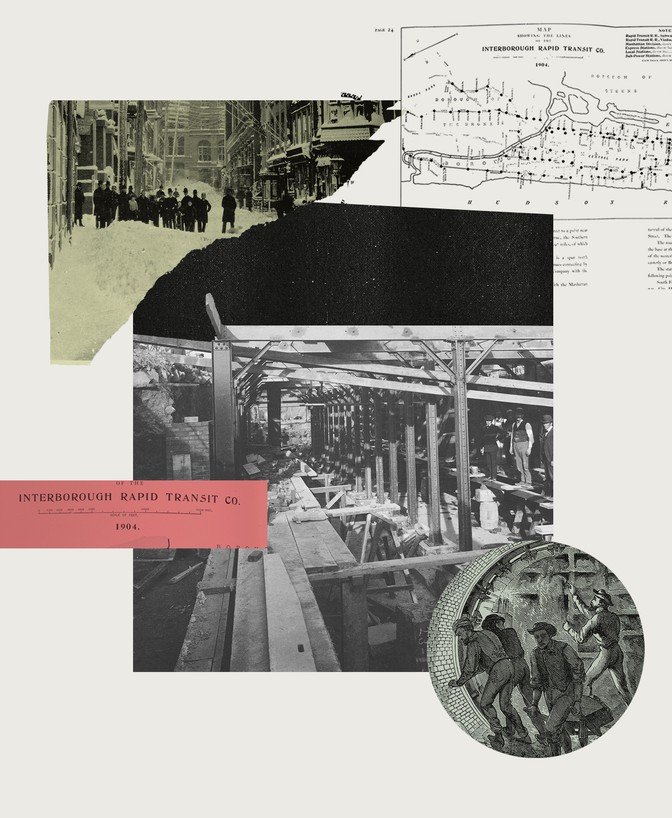

Second, and even more important, New York buried its elevated trains, creating the country’s most famous subway system. “An underground rapid transit system would have done what the elevated trains could not do,” The New York Times had written in the days after the blizzard, blasting “the inadequacy of the elevated railroad system to such an emergency.” Even without a blizzard, as Doug Most details in The Race Underground, New York’s streets were becoming impassable scrums of pedestrians, trolleys, horses, and carriages. The year before the blizzard, the elevated rails saw an increase of 13 million passengers. The need for some alternative—and likely subterranean—form of transportation was obvious. London had opened the first part of its subway system several decades earlier. In New York, the blizzard was the trigger.

“New York is built on disasters,” Mitchell L. Moss, a professor of urban policy and planning at NYU, told me recently. “There’s the 1835 fire, and the construction of the Croton Aqueduct. There’s the 1888 blizzard, and the construction of the subway. There’s the Triangle Shirtwaist fire, which killed 146 workers in Manhattan. Frances Perkins would say, ‘The New Deal started with the factory fire,’ because it was the disaster that led to a New York State commission on labor conditions, which in turn led to the eight-hour workday. In all of these physical disasters, New York City has responded by changing for the better.”

Read: How Frances Perkins, the first woman in the U.S. Cabinet, found her vocation

In October 1904, after years of political fights, contractor negotiations, and engineering challenges, New York’s first subway line opened. In a lightning-bolt shape, it ran north from city hall to Grand Central Station, hooked west along 42nd Street, and then turned north again at Times Square, running all the way to 145th Street and Broadway, in Harlem. Operated by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company, the 28-stop subway line was known as the IRT. Just months later, New York faced a crucial test: another massive winter storm. As the blizzard raged, the IRT superintendent reported “446,000 passengers transported,” a record daily high achieved “without a single mishap.”

Finding Our Inner Chadwick

Not all calamities summon forth the better angels of our nature. A complete survey of urban disasters might show something closer to the opposite: “Status-quo bias” can prove more powerful than the need for urgent change. As U.S. manufacturing jobs declined in the latter half of the 20th century, cities like Detroit and Youngstown, Ohio, fell into disrepair, as leaders failed to anticipate what the transition to a postindustrial future would require. When business districts are destroyed—as in Chicago in 1871—an influx of capital may save the day. But when the urban victims are poor or minorities, post-crisis rebuilding can be slow, if it happens at all. Hurricane Katrina flooded New Orleans in 2005 and displaced countless low-income residents, many of whom never returned. Some cataclysms are not so much about bricks and mortar as they are about inequality and injustice. “Natural disasters on their own don’t do anything to stem injustice,” observes Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, a professor of African American studies at Princeton. “Without social movements or social upheaval, the recognition of inequities never progresses beyond an acknowledgment that ‘We have a long way to go.’ ”

Still, catastrophes can fix our minds on a common crisis, pull down political and regulatory barriers that stand in the way of progress, and spur technological leaps, bringing talent and money together to solve big problems. “Disasters reveal problems that already existed, and in doing so, create an opportunity to go back and do what you should have done the first time,” Mitchell Moss said. New York City didn’t have to suffer a devastating fire in 1835 to know that it needed a freshwater source. Nonetheless, when Lower Manhattan burned, city leaders were persuaded to act.

Normal times do not offer a convenient news peg for slow-rolling catastrophes. When we look at the world around us—at outdated or crumbling infrastructure, at inadequate health care, at racism and poverty—it is all too easy to cultivate an attitude of small-minded resignation: This is just the way it has always been.Calamity can stir us from the trance of complacency and force us to ask first-principle questions about the world: What is a community for? How is it put together? What are its basic needs? How should we provide them?

These are the questions we should be asking about our own world as we confront the coronavirus pandemic and think about what should come after. The most important changes following past catastrophes went beyond the catastrophe itself. They accounted fully for the problems that had been revealed, and conceived of solutions broadly. New York did not react to the blizzard of 1888 by stockpiling snow shovels. It created an entire infrastructure of subterranean power and transit that made the city cleaner, more equitable, and more efficient.

The response to COVID-19 could be similarly far-reaching. The greatest lesson of the outbreak may be that modern cities are inadequately designed to keep us safe, not only from coronaviruses, but from other forms of infectious disease and from environmental conditions, such as pollution (which contributes to illness) and overcrowding (which contributes to the spread of illness). What if we designed a city with a greater awareness of all threats to our health?

The responses could start with a guarantee of universal health care, whatever the specific mechanism. COVID-19 has shown that our survival is inextricably connected to the health of strangers. Because of unequal access to health care, among other reasons, many people—especially low-income and nonwhite Americans—have been disproportionately hard-hit by the pandemic. People with low incomes are more likely than others to live in multigenerational households, making pathways of transmission more varied. People with serious preexisting conditions have often lacked routine access to preventive care—and people with such conditions have experienced higher rates of mortality from COVID-19. When it comes to infectious diseases, a risk to anyone is a risk to everyone. Meanwhile, because of their size, density, and exposure to foreign travelers, cities initially bore the brunt of this pandemic. There is no reason to think the pattern will change. In an age of pandemics, universal health care is not just a safety net; it is a matter of national security.

City leaders could redesign cities to save lives in two ways. First, they could clamp down on automotive traffic. While that may seem far afield from the current pandemic, long-term exposure to pollution from cars and trucks causes more than 50,000 premature deaths a year in the United States, according to a 2013 study. Respiratory conditions aggravated by pollution can increase vulnerability to other illnesses, including infectious ones. The pandemic shutdowns have shown us what an alternative urban future might look like. Cities could remove most cars from downtown areas and give these streets back to the people. In the short term, this would serve our pandemic-fighting efforts by giving restaurants and bars more outdoor space. In the long term, it would transform cities for the better—adding significantly more room for walkers and bicycle lanes, and making the urban way of life more healthy and attractive.

Second, cities could fundamentally rethink the design and uses of modern buildings. Future pandemics caused by airborne viruses are inevitable—East Asia has had several this century, already—yet too many modern buildings achieve energy efficiency by sealing off outside air, thus creating the perfect petri dish for any disease that thrives in unventilated interiors. Local governments should update ventilation standards to make offices less dangerous. Further, as more Americans work remotely to avoid crowded trains and poorly ventilated offices, local governments should also encourage developers to turn vacant buildings into apartment complexes, through new zoning laws and tax credits. Converting empty offices into apartments would add more housing in rich cities with a shortage of affordable places to live, expand the tax base, and further reduce driving by letting more families make their homes downtown.

Altogether, this is a vision of a 21st-century city remade with public health in mind, achieving the neat trick of being both more populated and more capacious. An urban world with half as many cars would be a triumph. Indoor office and retail space would become less valuable, outdoor space would become more essential, and city streets would be reclaimed by the people.

“Right now, with COVID, we’re all putting our hopes in one thing—one cure, one vaccine—and it speaks to how narrow our vision of society has become,” says Rosner, the Columbia public-health historian. His hero, Chadwick, went further. He used an existential crisis to rewrite the rules of modern governance. He shaped our thinking about the state’s responsibility to the poor as much as he reshaped the modern city. We should hope that our response to the 2020 pandemic is Chadwickian in its capacity to help us see the preexisting injustices laid bare by this disease.

One day, when COVID-19 is a distant memory, a historian of urban catastrophe might observe, in reviewing the record, that human beings looked up, to the sky, after a fire; looked down, into the earth, after a blizzard; and at last looked around, at one another, after a plague.

This article appears in the October 2020 print edition with the headline “How Disaster Shaped the Modern City.”

* Illustration by Mark Harris; images from Interborough Rapid Transit Company; National Weather Service; Wiley & Putnam / Artokoloro / British Library / Alamy; Thomas Kelly / Library of Congress

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário