(sublinhados meus)

Why I’m fighting to ban smartphones for children

Sophie Winkleman has narrated this article for you to listen to.

I am not often lost for words, but the five middle-aged homeless men who spoke at the Big Issue celebration in the House of Lords last month left me truly awestruck. All five had endured lives of childhood abandonment, violence, pain, destitution. All five had emerged from the darkness philosophical, hopeful and loving of their fellow man. I have not stopped thinking about them, and when I start on my usual daily beefs – signs on the Tube telling me I mustn’t give money to beggars (why not if I want to?); signs on the Tube telling me I can’t stare at people (what if someone is listening to a deafening violent video on their phone, should I deck them instead?); signs on the Tube telling me I mustn’t press into someone (try the Victoria line at 6 p.m., you TfL halfwits) – I think of these brave, strong men and I breathe in deeply.

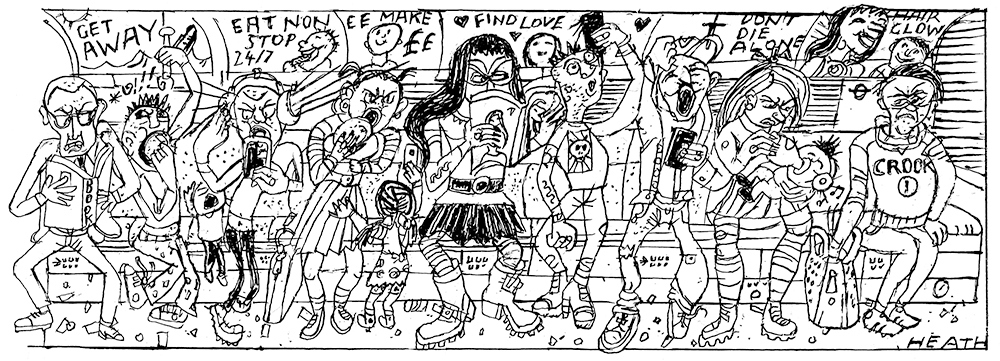

I’m seeing these daft Tube signs rather a lot lately. My life is now hopping on the District line to Westminster for a daily fight to ban smartphones and social media for under-16s, along with a gang of cross-party MPs, writers, teachers and doctors. The facts are so bleak – the failing eyesight, wrecked concentration spans, antisocial behaviour, insomnia, depression, self-harm, anorexia, porn and gaming addictions and worse. The teens I’ve met across the country (in my role as patron of an education charity) are desperate for the damn things to be taken away. Many libertarians think the onus should be on parents to ban smartphones, not the government. That’s fair enough in principle, impossible in practice. Every atom of a teen’s life is online: travel card, bank card, social life, even homework. These machines are designed by geniuses to be more addictive than heroin – it’s not possible to put them down. Sure, middle-class parents can beg their teens to put their phone away each night, but what about our poorer children whose parents can’t always supervise them? They’re the ones whose life chances are being destroyed by the compulsive, pointless, damaging junk on smartphones, and they must be protected. The Online Safety Bill won’t go nearly far enough. It may remove some harmful content, but it won’t touch the sides of the unputdownable, isolating, focus-wrecking nature of these phones.

Another major factor in the degradation of children’s minds is the shift to digital education. This should have been an emergency move during lockdown, then straight back to books, paper and pens. Most intelligent countries are chucking tech out of the classroom as overall progress and IQ levels glide downwards like dying birds. Here in Britain, far more scepticism should be applied to these shiny platforms which serve only to stoke screen addiction, further damage eyesight and encourage shallow, short-form thinking.

It was lovely to bump into a fellow fighter in the anti-screens movement yesterday. Daisy Greenwell and I walked straight into each other on Quay Street in Orford, Suffolk, where I’ve come to visit my parents for Easter. Fortunately, our children were all walking the no-tech walk – mine up a tree, hers sandy, tousled and clutching buckets and spades. We embraced as old friends, though we’ve never met before. I’ve joined her and Clare Fernyhough’s triumphant movement Parents for a Smartphone-Free Childhood and she’s read some of my scribblings – an instant bond founded on a common goal and a shared god in the form of Jonathan Haidt, psychologist and author of our bible, The Anxious Generation. Perhaps the most frustrating refrain we hear in this fight is ‘the genie is out of the bottle’. Such defeatism confounds us. We are talking about mass social, educational, cognitive and developmental harm. In other words, mass brain damage. We have the bottle; we must cram the genie back in.

Out here in somnolently peaceful, pure-aired Orford, I feel I can breathe. The glorious 14th-century church, the fairytale castle built by Henry II, the village shop with its locally made pork pies and fairy-cakes, the allotments chirruping with chiffchaffs, tits and finches, banks of nodding daffodils and endless vistas of flat, dreamy waterscapes – it all fills me with love for England. While I like meeting strangers every day in London, the sight of village regulars I’ve known for 30 years is calming to the spirit. From Guy the churchwarden who takes my girls up to the bell-tower, to Adrian the fisherman who delivers me a dozy lobster every time I’m in the village, to Laura, who can carry two 20kg sacks of salt as if they’re babies, and Sue, who always saves me a box of those fairy-cakes – it’s a blessed respite from the bustling solipsism of the Big Smoke. Right, off to visit the Palm Sunday donkey now. Happy Easter everyone.

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário