What David Attenborough’s ‘Wild Isles’ doesn’t tell you

It is not just Gary Lineker, apparently, who has fallen victim to sinister right-wing forces at the BBC. A follow-up programme to David Attenborough’s BBC1 series Wild Isles, focusing on the decline of UK wildlife, will not be shown on terrestrial television but only made available on iPlayer. ‘The decision has angered the programme-makers and some insiders at the BBC,’ reports the Guardian, ‘who fear the corporation has bowed to pressure from lobbying groups with “dinosaurian ways”.’

The BBC has claimed that the extra programme – which, like the whole of the Wild Isles series, is co-produced by the WWF and the RSPB – was never intended to be shown on BBC1. But if the BBC really was a little concerned that Wild Isles might be in danger of laying on its claims of environmental degradation a little too thickly, it would have good reason. While the extra programme has yet to be released on iPlayer, the first episode of Wild Isles broadcast on BBC1 on 12 March, contained an extremely dubious claim of its own.

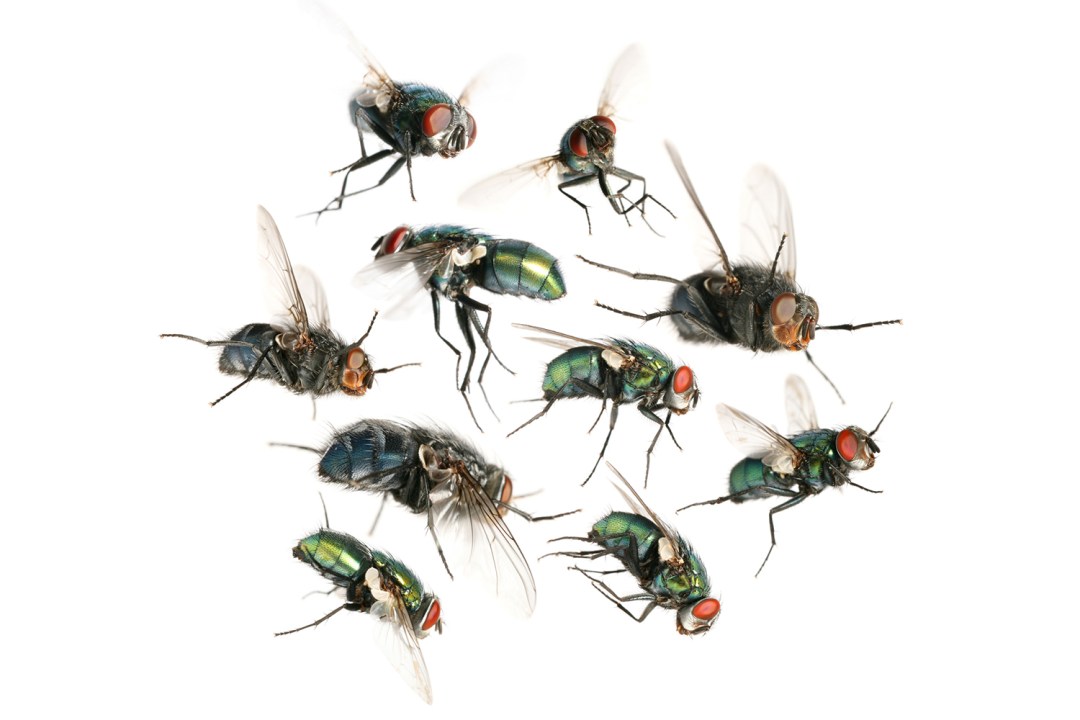

Set against a scene of bluebells, Attenborough stated that: ‘In just the last 20 years, 60 per cent of our flying insects have vanished.’ It was an alarming statistic which spoke of fast-approaching doom. If insects were to die out, we would be surrounded by an awful lot of undecayed vegetable matter. Coming from one of the most trusted voices on television, the claim will have been accepted by many viewers as unquestionable fact.

But is it really? The BBC failed to answer where the programme had sourced the claim, but it is likely to have come from a study conducted by a nature conservation charity called Buglife, along with the Kent Wildlife Trust, in 2021, which has never been published in a peer-review journal. As a piece of ‘citizen science’, encouraging the public to get involved in research exercises, it might have some merit. As a piece of science, it is not exactly going to win its authors a Nobel Prize. Indeed, its methodology raises multiple red flags which should be obvious to anyone with the most basic grasp of science.

What Buglife and the Kent Wildlife Trust did was to ask the public to wash their front number plates before they set out on a car journey and then count the number of dead insects stuck on the plates after arriving at their destination. The results were then compared with a similar exercise conducted in 2004. In 2021, there were 0.104 ‘splats per mile’. The 2004 study, by contrast, had recorded 0.238 splats per mile. These crude figures, with a little adjustment for time of day and a few other variables, were then used to arrive at the claim that there has been a 58.5 per cent reduction in flying insects over the 17 years from 2004 to 2021 – ranging from 27.9 per cent in Scotland to 65 per cent in England.

To be fair to the authors, they do acknowledge many of the inadequacies of their study. Insect populations, for example, are highly variable from year to year and from season to season. As anyone who has been camping in the Highlands can attest, populations of flying insects can explode one week and seemingly disappear the next. It therefore tells us little to compare statistics from just two years and then suggest that the results constitute a trend.

Moreover, a study of insects splatted on number plates tells us nothing about the insect population in Britain as a whole, only that in close proximity to roads. And roads vary enormously. You might expect to encounter very different populations of insects on, say, the North Circular compared with a lane in rural Shropshire.

Yet the Buglife study doesn’t standardise the manner in which data was collected. Indeed, the average speed of journeys which constituted the 2004 study was 37.2mph compared with 29.3mph in the 2021 study. Should it really be a surprise that vehicles travelling at higher speeds might squash more insects?

The data was collected using anything from sports cars to HGVs, the latter of which were found to have a ‘splat rate’ half as high again as for cars. Whether an insect ends up stuck on a vehicle number plate has rather a lot to do with the aerodynamics of the vehicle. The study attempts to correct the results for some of these variables, but a study based on just 3,300 journeys in 2021 produces only so much data. The study does not even take into account traffic levels. If you are driving along an empty road, you are inevitably going to capture more insects than if you are in traffic, as in the latter case the insects that are present will be shared out among other vehicles. A proper study would also ensure that the surfaces used to capture insects were standardised, as an insect is more likely to adhere to some materials than to others. Some older number plates are aluminium, while modern ones tend to be acrylic.

To give Buglife’s authors credit, they do state in their study that: ‘Over-simplified reporting by the media of negative trends from short-time series data such as those presented here risks missing some of the nuances and limitations of research… We recognise and stress that the results we have reported here do not constitute a trend, and advocate strongly for data collection over extended timeframes to enable conclusions about insect populations to be drawn.’ The producers of Wild Isles, however, ignored all this and presented the 60 per cent figure as if it were plain fact.

As it happens, there have been proper studies of changing insect numbers in Britain over the past half-century, conducted using standardised methods. There have been some declines, but nothing like to the extent claimed by the Buglife study. The Rothamsted Insect Survey, which has been going since 1964, recorded a 33 per cent decline in numbers of large moths between 1968 and 2017, with a bigger fall in the south than the north. Of the 427 species studied, 41 per cent had declined in number over that period and 10 per cent had increased.

Yet the parallel UK Butterfly Monitoring Scheme, which has been going since 1976, has a different story to tell, with 2019 the eighth best for butterflies in 44 years. One species, the marbled white, had its best year ever recorded, with numbers 66 per cent up on the previous year, a statistic that underlines how careful you need to be when assessing trends in insects, given how up and down they tend to go. A 2019 study by the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology found that of 353 species of bees and hoverflies, a third had declined since 1980 and 10 per cent had increased. Species which pollinate particular agricultural crops had done well, while rare species had declined. There is limited data on other insects.

There may well be reason to worry about the decline of some species, insects included. There are also some reasons to be optimistic about insects, given that the world’s vegetation is steadily growing more vigorous as CO2 levels rise: more plants mean more food. Pesticides, too, are becoming more discerning in what they kill. Yet none of this comes through in Wild Isles. The series may be beautifully shot, but it is presented against a backdrop of gloom, of wildlife in sharp decline.

Where a species has suffered a fall in numbers, that is mentioned, but where one has proliferated in recent decades – such as deer – it goes unacknowledged. Given the popularity of Attenborough’s programmes, and the effect that doom-laden claims about the climate and other environmental matters seem to be having on young people, you might think the BBC would want to make sure every claim in Wild Isles was fair and accurate. Sadly, this does not appear to be the case. When shown this article, and given the chance to respond, the BBC chose not to reply.

Ross Clark’s Not Zero: How an Irrational Target Will Impoverish You, Help China (and Won’t Even Save the Planet) is out now.

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário