Is wrestling an art?

It isn’t easy selling out Wembley Stadium with its capacity of between 70,000 and 90,000 (depending on the exact arrangement). It’s a feat achieved by only a handful of performers each year – all of whom you’ve likely heard of.

This summer, though, Wembley will play host to something rather different – an American pro wrestling show called AEW (All Elite Wrestling). A few months ago, AEW’s biggest achievement this side of the Atlantic was bagging a midnight slot on ITV4. Now it’s going head to head with Harry Styles on ticket sales.

Arguably, AEW isn’t even the most important wrestling event in Britain this year. Next Saturday, the US-based World Wrestling Entertainment – the granddaddy of American wrestling – will host its first ‘premium’ event in London for 30 years at the Greenwich O2. The 18,000 or so tickets sold out in an hour, with most fetching well into triple figures.

No wonder that Hollywood executive Ari Emanuel recently finalised a deal to acquire WWE – which has one billion social media followers worldwide – for more than $9 billion. For context, that’s more than double what Disney paid to acquire Star Wars (in 2012), and three times the entire estimated value of ITV.

The numbers speak for themselves. But there’s a more important question: what is wrestling – and can you call it art?

If the old cliché is to be believed, then what happens in the ring is little more than a ‘soap opera in spandex’ – a quote trotted out by the Bafta-winning comic Stephen Merchant when he wrote and directed Fighting with My Family, a 2019 film about a British family auditioning for WWE. But for the French philosopher and essayist Roland Barthes, wrestling was something much more powerful – ‘a spectacle of excess’ on a par with the theatre of ancient Greece.

‘It’s like a TV drama with all of the athleticism of gymnastics and dancing thrown in together,’ enthuses Alex Davies-Jones, the Labour MP for Pontypridd, a long-time wrestling fan who chairs a parliamentary group on wrestling. Last year, the group visited a WWE event in Cardiff where Tory MP Dehenna Davison wrestled fellow parliamentarian Christian Wakeford outside a pub.

Like Barthes, Davies-Jones praises the unashamed spectacle of live wrestling. Take this Saturday’s Money in the Bank event at the O2. The three-hour show will culminate in a seven-way scrap, in which brawling wrestlers compete to be the first to climb a ladder and retrieve a special briefcase (containing a contract for a future fight) suspended above the ring.

So far, so Gladiators. Yet a decent ladder match requires more than just wrestlers being willing to tumble from a height. The real thrill comes from the ways that the performers – some of whom possess near-superhuman levels of athleticism – make use of the environment around them. The best moments combine circus-like stunts with clever tactical manoeuvres that play with your expectations.

Of course, a good narrative requires solid characters too. While once upon a time wrestling fans may have cheered the wholesome patriotism of Hulk Hogan, these days they’re likely to prefer someone like Rhea Ripley: a 26-year-old muscle-bound Australian goth – real name Demi Bennett – who recently became the WWE’s women’s champion.

Ripley isn’t just physically imposing; she’s also one of the most charismatic women in what the WWE carefully calls ‘sports entertainment’ (a subtle concession of the staged nature of wrestling). Last year, Ripley subverted the tradition of female stars serving as sidekicks to male counterparts by seemingly hypnotising the son of one of WWE’s most beloved veterans. He now functions as her valet, occasionally tripping up her competitors when the referee isn’t looking.

‘I think my character is very much me,’ she tells me over Zoom, proudly perched in front of her decorative WWE belt. ‘It’s just the side of myself that would get me arrested in real life.’ Does she take pride in how viscerally the fans react to her character? ‘Oh, it’s insane,’ she says. ‘Sometimes the booing is so loud I can’t even hear what my partner is saying. And he has a microphone.’

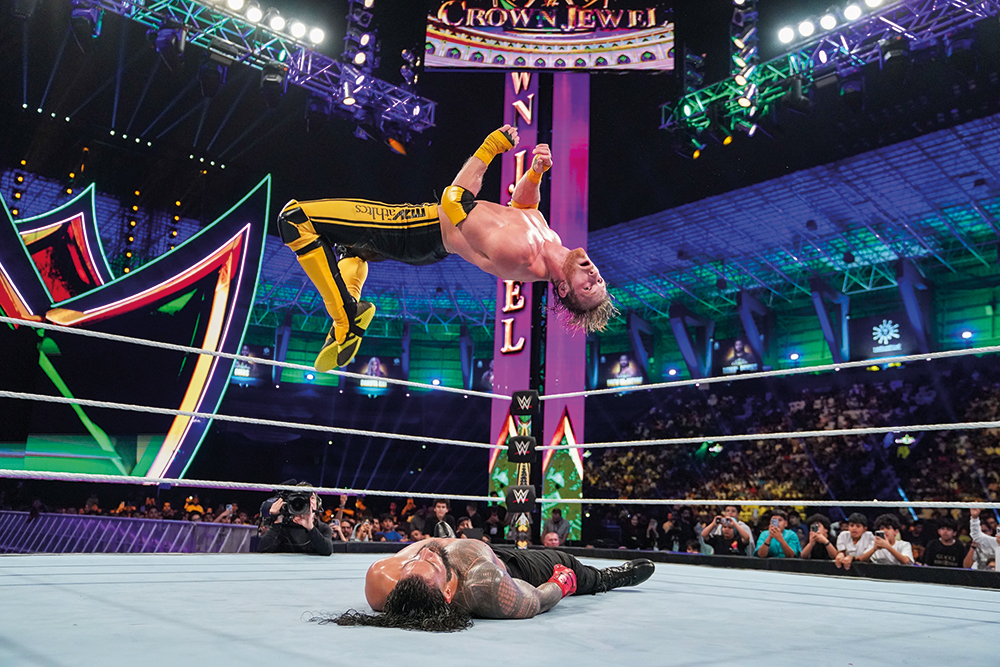

Other plotlines opt for more of a slow burn. Over the past year, the best story arc in WWE has been the Bloodline: an alliance of real-life family members whose dominance of the wrestling landscape finds itself threatened by the hubris of its leader Roman Reigns (the current WWE men’s champion and a dead ringer for Aquaman actor Jason Momoa).

On paper, the Bloodline affair hasn’t strayed far from familiar wrestling territory: it remains, at heart, a story about muscular men seeking glory. Yet the execution has been much smarter, slower and more nuanced than anything before it. All of a sudden WWE feels less soap opera and more ‘prestige television’.

Perhaps that’s no coincidence. Twenty years ago, wrestling storylines were generally hammered out by large men in sweaty locker rooms. These days they’re usually written by professional screenwriters. Last year, the WWE poached an ex-Marvel writer as its new ‘director of long-term creative’: a revealing sign as to its future ambitions.

The WWE used to be notoriously tight-lipped about its creative processes. Throughout the 1980s, it refused even to admit that wrestling was scripted. Yet its current executives have praised the present direction. One recently called for the Bloodline arc to be nominated for an Emmy – where it would end up against the likes of Succession; another called the storyline ‘Shakespearean’ in its ambition.

For wrestling purists, some of whom rankle at any comparison between wrestling and the traditional performing arts, it has been somewhat of a journey. The pundit Jim Cornette – a legendary WWE promoter turned acerbic podcast host – recently objected to his co-host praising ‘the acting’ in WWE. Cornette put the wrestling universe straight: praise the delivery if you must, but never call it acting.

Then there’s the parallel world of independent wrestling – some of which deliberately rebels against the mainstream appeal of WWE and AEW. Last year, a Conservative club in Seaham, County Durham issued an apology after renting out its premises to a small wrestling show, only to end up hosting a ‘deathmatch’ – a hyper-violent style of weapons-based combat in which performers aim to draw real blood.

Deathmatches aren’t pretty, but they are on the rise – partly due to DIY streaming platforms which let promoters monetise their shows online. The security guard in my local Sainsbury’s moonlights as a deathmatch wrestler called ‘Big F’n Joe’. As well as appearing in UK shows, he is regularly flown out by American promoters to participate in fights there. Videos on YouTube show him being thrown through a makeshift table of glass light-tubes.

‘If wrestling is rock music, then deathmatch is Scandinavian black metal,’ he tells me over the phone from sunny Great Yarmouth. In other words, it isn’t for everyone. But is it still art? Amusingly enough, some deathmatch promoters in the US class their events as ‘performance art’ in order to avoid having to obey the rules of state athletic commissions (who may have an opinion on the broken glass).

It’s a world away from next weekend’s family friendly WWE show, where the YouTube celebrity Logan Paul is set to enter the big ladder match. With 27 million subscribers and a net worth of $45 million, the 28-year-old probably falls into the category of being rich enough to do whatever he wants – and as a lifelong wrestling fan he’s doing just that.

In an 1972 essay, Barthes praised the power of wrestling to elevate its performers above the ‘constitutive ambiguity’ of everyday situations, turning them into temporary gods of good and evil. The sight of a pampered internet celebrity being thrown from a 12ft ladder might not have been what he had in mind. But I suspect he’d have liked it nonetheless.

Money In The Bank is available on the WWE Network from 1 July. AEW All In comes to Wembley Stadium on 27 August.

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário